(1867 – 1951)

From a small village in Ireland, Amy Carmichael came to the hot, dusty streets of India with just a soul full of enthusiasm for the Lord. She was a lady with a heart full of faith and a head full of common sense. She believed with all her heart and was willing to go gritty depths for the children she loved. She believed in Calvary Love and understood that it takes God to do all things and so adopted truth led actions with love rather than words or speech.

Youthful Escapades

Amy Wilson Carmichael was born in the small village of Millisle, County Down, Ireland in 1867 to David Carmichael, a miller, and his wife Catherine on December 16, 1867. Her parents were devout Presbyterians, and she was the oldest of seven siblings.One of the most famous stories associated with Amy is a possibly apocryphal tale of how she earnestly wished for blue Irish eyes rather than the plain brown ones she was born with. She was told by her mother that the Lord would answer if she prayed and so she did. Her mother heard her wail in disappointment when Amy ran to the mirror the next morning and found no change. It took Mrs. Carmichael several minutes of careful explanation before Amy understood that "no" was an answer too. Mrs. Carmichael explained that God meant Amy to have brown eyes for a reason even though she didn't understand why at that time.

As a young girl, Amy was quite the rebel ringleader and easily could be traced as the perpetrator of any mischief that took place in the house. One time, squeaks interrupted the family devotions. Amy feigned ignorance, but it became known that a frozen mouse carried in her pocket got revived.

Another time she led her brothers and sisters in a challenge to see how many poisonous laburnums pods they could eat before they died. However, they survived after bout of upset stomachs. There was another time when she led them through a skylight onto the dangerously slippery slope of the roof.

Critical Life Changes

Growing up in a devout household Amy was taught to be a true Christian but she became aware of more personal commitment by a visiting evangelist. Amy was convicted and gave her heart to the Lord and vowed to be of service to Him.After three years at boarding school, Amy returned home to Belfast because her parents no longer had the money to support her education. Mrs. Carmichael took sixteen year old Amy out to buy a dress. Amy found a beautiful one -- royal blue -- but turned away from it. Her mother was surprised as Amy explained that clothes were no longer important to her as in past and that Christ had given her a new purpose in life. She would wait a year for her parents to be better placed to afford new clothes for her. Sadly, she never could get that dress, because the next year, Mr. Carmichael died unexpectedly.

Seeking And Saving The "shawlies"

That was the year that Amy started classes and prayer groups for Belfast ragamuffins. She also began Sunday work with the "shawlies" in the church hall of Rosemary Street Presbyterian. These were factory girls so poor that they could not afford hats to wear to church and wore shawls instead. Respectable people didn't want anything to do with them. Amy saw that they needed Christ just the same as their supposed "betters." Eventually so many shawlies attended Amy's classes that she had to find a building large enough to hold three hundred and more. At this time Amy saw an advertisement in The Christian, for an iron hall that could be erected for INR 44,649.95 and would seat 500 people. Two donations, INR 44,649.95 from Miss Kate Mitchell and one plot of land from a mill owner, led to the erection of the first "Welcome Hall" on the corner of Cambrai Street and Heather Street in 1887.The Carmichaels lost all their money through financial reverses and a change became necessary. Mrs. Carmichael decided to move to Manchester in England and work for their Uncle Jacob. Amy and another sister joined her where Amy was asked to teach the mill workers about Christ. Amy threw herself into the work, living near the mill in an apartment infested with cockroaches and bed bugs.

After this, she moved on to missionary work, although in many ways she seemed an unlikely candidate for missionary work, suffering as she did from neuralgia, a disease of the nerves that made her whole body weak and achy and often put her in bed for weeks.

It was at the Keswick Convention of 1887 that she heard Hudson Taylor speak about missionary life. Soon afterward, she became convinced of her calling to the same labour.

Leaving For Japan

So, for over a year, Amy tried to find a place to go, but no opportunities opened up.Nevertheless, she set off for Japan in the company of three missionary ladies, a letter having been sent ahead offering her assistance to missionaries there. She set sail on March 3, 1893, having obtained her mother's blessing.

Amy had a constant passion to witness for Christ and even the captain of the ship believed in the Lord after observing how cheerfully Amy faced the dirt and insects onboard.

Japan

Once in Japan, even before she learned the language, Amy went out to witness. Her interpreter, Misaki San, suggested that Amy wear a kimono, but Amy preferred her western dress and kept it on. The two visited a sick old woman who seemed interested in the Gospel. Just as Amy was about to ask her if she would repent, the woman caught sight of her fur-lined gloves and asked what they were. Driving home, Amy wept bitter tears and vowed never to put comfort above ensuring that the gospel got all prominence, a philosophy that stayed with her even in India. From then on, she wore Japanese clothes while witnessing.On another occasion, Amy and Misaki San were asked to send the spirit of the fox out of a violent and murderous man. Village priests had tried their formulas and tortures without success. Trusting that the Lord could drive demons away, the two girls prayed and went boldly into the man's room. As soon as they mentioned the name of Jesus, the man went into an uncontrollable rage. If he had not been tied, he would have leaped upon them. The two girls were hurried out from the room. Perplexed, they soon recovered their confidence. They assured the man's wife that they would pray until the spirit left and asked her to send a message when it was gone. Within an hour they received the message. The next day, the man himself summoned them, and over the next few days they explained the way of Christ to him, and he became a Christian.

Once when she was about to visit the Buddhist village of Hirose, Amy asked the Lord what she should ask of Him before she went and prayed for one soul. A young silk-weaver heard their message and became a Christian. Amy's neuralgia kept her in bed for a month after that. But the next time she went out, she again felt she must pray, and asked for two souls. The silk-weaver brought two friends, and they gave themselves to Jesus. Two weeks later, Amy felt to ask for four souls.

The visit went badly. Amy wondered if she hadn't mistaken an arithmetical progression for the leading of the Lord. No one seemed interested in the gospel. Not many came to the evening service. Amy was almost in tears. Suddenly the spirit changed. A woman spoke up and asked the way to Christ, and then her son came in and committed himself to the new religion also. At the home of some Christians that evening another woman accepted Christ and the next morning a fourth.

Amy fell ill again, this time for a month and a half. She felt led to ask for eight more souls to be added to the Lord. The other missionaries chided her. "It is not faith," they said, "but presumption." Amy insisted that the Lord himself had wrestled with her. She was terrified, she said, and would never ask this in her own strength.

Needless to say, eight souls took the Christian way on that visit. After this, her neuralgia worsened to the extent that she was advised to leave Japan for a more suitable climate.

On To India

After some struggle and confusion, Amy accepted that she would be better off in India and after fifteen months in Japan she was commissioned by the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society.It was not uncommon in India at the time for young girls to be given to the local Hindu temple. This saved the family of the girl money because they did not have to take care of the young one who was dedicated to the gods, and then usually forced into prostitution to earn money for the priests (i.e., made a Devadasi). This was a cause that was extremely close to Amy's heart and one that she undertook with a lot of zeal and fervour often with considerable risk to herself.

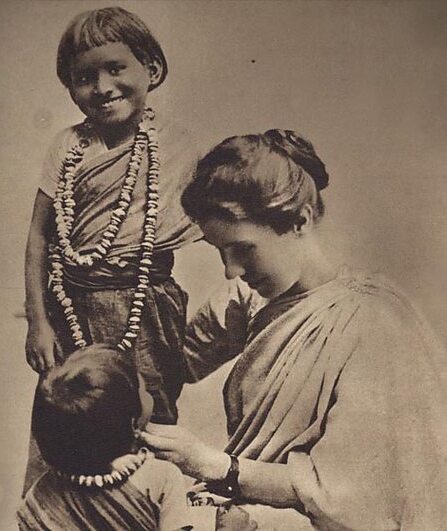

Amy often said that her Ministry of rescuing temple children started with a girl named Preena. Having become a temple servant against her wishes, Preena managed to escape. Amy Carmichael provided her shelter and withstood the threats of those who insisted that the girl be returned either to the temple directly to continue her sexual assignments, or to her family for more indirect return to the temple. The number of such incidents soon grew, thus beginning Amy's new Ministry. When the children were asked what drew them to Amy, they most often replied "It was love. Amma (Amy) loved us."

Soon, she had founded the Dohnavur Fellowship and provided a safe haven for over one thousand children who might otherwise die or be forced into prostitution and/or slavery. Given her devotion to pursuing and rescuing the abandoned children of India, it was no surprise that Amy insisted: "One can give without loving, but one cannot love without giving."

Respecting Indian culture, members of the organization wore Indian dress and gave the rescued children Indian names. Amy herself dressed in Indian clothes, dyed her skin with dark coffee, and often travelled long distances on India's hot, dusty roads to save just one child from suffering.

While serving in India, Amy received a letter from a young lady who was looking for life as a missionary. She asked Amy, "What is missionary life like?" Amy wrote back saying simply, "Missionary life is simply a chance to die."

Nonetheless, in 1912 Queen Mary recognized the missionary's work, and helped fund a hospital at Dohnavur. By 1913, the Dohnavur Fellowship was serving 130 girls. In 1918, Dohnavur added a home for young boys, many born to the former temple prostitutes. Meanwhile, in 1916 Carmichael formed a Protestant religious order called Sisters of the Common Life.

Amy's work also extended to the printed page. She was a prolific writer, producing thirty-five published books including His Thoughts Said . . . His Father Said(1951), If (1953), and Edges of His Ways (1955). Best known, perhaps, is an early historical account, Things As They Are: Mission Work In Southern India (1903).

In 1931, Amy was badly injured in a fall, which left her bedridden much of the time until her death. Amy Carmichael died in India in 1951 at the age of 83. She asked that no stone be put over her grave; instead, the children she had cared for put a bird bath over it with the single inscription "Amma", meaning mother in Tamil.

Her example as a missionary inspired others (including Jim Elliot and his wife Elisabeth Elliot) to pursue a similar vocation. Many web pages include quotes from Carmichael's works, such as, "It is a safe thing to trust Him to fulfil the desire that He creates."

India outlawed temple prostitution in 1948. However, the Dohnavur Fellowship continues, now supporting approximately 500 people on 400 acres with 16 nurseries and a hospital, continuing the legacy of Amy Carmichael.

– Michelle Sunny Parayil

This article originally appeared in the Harvest Times magazine's August 2016 issue.